Mattie’s Story

Charles G. Gosselink

Preface

The following is a true story. It is based on the facts as far as we have been able to determine them, from public records, letters, and internet sources. Because the facts are few, I have had to read between the lines and rely on creative imagination in order to tie things together, but I hope I have not done an injustice to the truth. I have frequently used qualifiers: perhaps, might have, would have, most likely, and so on. These tend to make the writing a little heavy, but they will help the reader distinguish between facts and speculation.

I am grateful to Bob Busk, Paul Penfield, and Holly Mertz for helping to uncover this piece of family history. We are all indebted to Bob Busk for bringing the first fragments of the story to our attention and then tracking down the hard census data and other records which enabled us to develop a fairly complete narrative.

This is essentially a family story, but it does shed light on the broader picture of life in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century era. It was a period of rapid economic and political change, an optimistic time when people, driven usually by their Christian faith, really believed they could change their world for the better and were ready to act on that conviction. Our ancestors were deeply involved in movements of social reform, and this story reflects their beliefs, values, aspirations, and, yes, their shortcomings and blind spots. We do not need to assess praise or blame. This is simply the way the story unfolded.

Chuck Gosselink

June 10, 2007

This revised version of the story includes some changes and additions made necessary by the recent discovery more information.

CGG June 1, 2008

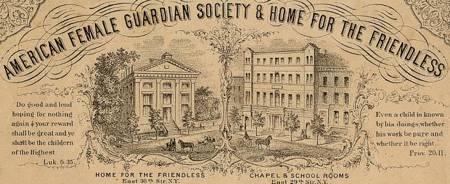

Cover Picture: The Home for the Friendless of the American Female Guardian Society, at East 30th Street and Madison Avenue, New York City. Lithograph by Francis Michelin and J.L. Shattuck, c. 1853-54. See the appendix for additional pictures of the Home for the Friendless and the Chapel and main offices of the Guardian Society.

Introduction

Very few members of our branch of the Penfield family living now had the good fortune to know Grandmother Charlotte Devins personally. Most of us are acquainted with her, if at all, through the letters she wrote when she and her husband Thornton Bigelow Penfield went as missionaries to India in 1866. We also have photographs and correspondence and some family stories and we remember that she helped make possible the purchase of the family cottage at Silver Bay. After her husband and new born baby died in India in 1871, she brought her two surviving children, Thornton and Irene, back to her parents’ home in Montclair, New Jersey. To support herself and her children, she took a job in New York City as the associate director of the American Female Guardian Society and Home for the Friendless, leaving her children in the care of her parents and sister Fannie during the week and returning to spend time with them on the weekends.

It was at the Home for the Friendless in 1876 that she first met John Devins. He was born in 1856. When he was only three, his mother, and another woman who had been caring for him, had given him up for adoption through the Home for the Friendless and he had been placed with a family in Oneida County, New York. Now as a young man he had returned to see the records of his adoption and learn something, if he could, about his parents. Charlotte helped him find what little information was available. In spite of their difference in age, she was twelve years older than he, they were immediately attracted to each other. While studying at New York University and working full time at the New York Tribune, he found time to visit her often, in New York and Montclair, and got to know her children. They were married in 1883, after he completed his degree.

It seems to have been a very happy marriage. They shared the same values and interests and strong Christian faith. He began his studies at Union Seminary and continued writing for the Tribune. She may have continued as a volunteer at the Home for the Friendless for a few years. After completing seminary, he was called to Hope Chapel on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, where he served the working class and immigrant population of that area. They lived in an apartment over the chapel and later moved to another small apartment just two blocks away. John was very active in the community, looking after the needs of his parishioners, establishing a relief program for the thousands affected by the crash of 1893, finding employment for many in work projects which he organized, addressing the need of strangers he met on the street, serving as counselor to the American Female Guardian Society, and working with the Tribune Fresh Air Fund to enable underprivileged children from New York City to spend some time in the country. There was hardly a good cause that he was not involved in – and he seems to have been an able administrator because his many projects were invariably successful.

For the first years of their marriage, Charlotte’s son Thornton was away at school at the St. Johnsbury Academy in Vermont, but Irene lived with them in New York. Tragically, she died of measles in 1885. When Thornton finished high school, he returned to New York and lived with his parents while attending Columbia University. He followed his step-father’s path to Union Seminary and employment with the New York Tribune. After seminary he accepted a position with the Presbyterian Board of Home Missions and later with the International Committee of the Y.M.C.A. In 1894 he married Martha Mee Martin. They lived in Brooklyn and were able to keep in close touch with his parents. Charlotte accepted Martha as her own daughter, and indeed she was hardly more than a year older than Irene would have been. When the children began to arrive, Charlotte became a devoted grandmother, writing frequently (in that era before the telephone) to inquire about their health and progress and cherishing the opportunities to look after them when their parents were away.

John and Charlotte Devins were frequently away, also. Every summer they attended the Missionary Conference in Northfield, Massachusetts. She often accompanied him on other trips within the United States and to Europe which he made on behalf of the Presbyterian Church or the Tribune. In 1903-4 they took a tour around the world, extending their time in the Philippines, the basis of his book, An Observer in the Philippines, 1905, and visiting the sites in India where she had been with Thornton Penfield and where her children were born. Later they took a cruise in the Mediterranean, the basis of his book, The Classic Mediterranean, 1910. He dedicated that book to his wife:

The noblest of women

The best of comrades

The truest of friends

In 1902 John had given up his position at Hope Chapel and his association with the Tribune to become editor of the Presbyterian paper, The New York Observer. He continued as Manager of the Tribune Fresh Air Fund, a cause very close to his heart, to which he gave a great deal of time and energy. He died quite suddenly in 1911. He was 55 years old. Some time later, Thornton and Martha invited Charlotte to make her home with them. She lived with them in Englewood, New Jersey until her death, at 88, in 1932.

This is the story of Charlotte and John Devins that the family remembers, fleshed out in more detail from a biography, John Bancroft Devins, A True Greatheart, written by E. C. Ray in 1912. What is very surprising is the lack of any reference in this narrative, or in the collective memory of the family, to John and Charlotte Devins’ daughter, Martha Allen – Mattie.

The Search

It began, as things often do these days, with an e-mail message from an unknown person in an undisclosed location to Paul Penfield:

Bob Busk is looking at the Penfield Family Web page on August 19,

2006:

Martha, who was born on August 19, 1883, was raised by John and Charlotte Devins in New York City as their own, and listed in the

1900 Census as their child. Does any of your research mention her?

Thank you.

Bob’s follow up message of August 24 added some details:

Perhaps I should have provided more information. Martha is my grandmother, and to the best of my knowledge John Devins is my

great grandfather. The 1900 New York County Census . . . taken on

4 June 1900, for 138 E. 2nd Street, indicates residents as follows:

Devins, John B Head

Charlotte E. Wife

Martha Daughter

Dable, Lizzie Lodger

You can hear the rustling in the Penfield genealogical tree. Is this another unknown branch of the family? A skeletal leaf in the closet? Or a case of mistaken identity? Marthas we have aplenty, but does anyone know of this Martha? Paul directed the question to Holly Mertz and me.

In fact, I had a quick answer. In the course of sifting through the files from the Birch Glen attic some time ago, I had come across a formal document, issued by The American Female Guardian Society of New York City, showing that John and Charlotte Devins had adopted a nine year old girl, Martha Allen, on March 25, 1892.

Today we might call it a foster care arrangement. John and Charlotte Devins agreed to take Martha into their care until she reached the age of eighteen. According to the contract, during all the time she lived with them, Martha, “according to her power, wit and ability” should honestly and obediently in all things demean herself “as all children should demean and behave themselves toward their natural parents”. John and Charlotte Devins agreed to provide Martha with all things necessary and fit for a child, as they would ordinarily do for their own children. They agreed to educate her “in all branches of education ordinarily taught to the children of persons in (their) station of life”, and, at the expiration of the term of adoption, to give her a complete new suit of clothes, together with those she already had, and the sum of sixty dollars. Finally, “They shall cause said child to attend public worship at least once a week (whenever such attendance is not too inconvenient); and shall bring her up in a moral and correct manner, and generally (undertake) that said child shall be maintained, clothed, educated, and treated with like care and tenderness as if she were in fact the child of the (adopting) party.”

At the time of the 1900 census, Martha was seventeen and near the end of her term of adoption. The following year, she would be free to leave the Devins family, to take her suit of new clothes and her sixty dollars and go off on her own. When I first found and read the adoption papers, that is exactly what I thought had happened. Martha had gone her own way. John and Charlotte Devins had closed that chapter of their lives.

But on further reflection, it did seem a little odd. We would expect that after nine years, mutual ties of love and affection would hold Martha close to her adoptive parents and she would not readily leave the care and tenderness she had found in the Devins home. And if for some reason she did leave and go her own way, we might expect John and Charlotte to hold some fond memories of their “daughter”, to tell stories of that time, and perhaps express some regrets that Martha was no longer with them. We might think that their son Thornton Penfield, who also lived in New York during those years and must have visited his parents’ home frequently, would have told his own children about his adopted sister or mentioned her in his memoirs. In fact, there is only silence. The census record and the adoption document seemed to be the only evidence that Martha was ever a part of the family. Later Holly found a reference in Grandmother Devins’ Red Letter Days book for March 10: “Mattie Allen came in 1891.” That would be a year before she was formally adopted, consistent with the American Female Guardian Society’s practice of requiring a year’s waiting or testing period. Still, there is, among the Penfield descendants of Grandmother Devins, no memory of Martha, or Mattie, Allen. She was there, and then she was gone.

Bob Busk’s family, on the other hand, had a somewhat better memory of Martha and her relationship with John and Charlotte Devins. Drawing on information that he had tracked down from public records or heard from his uncles and aunts, Bob continued the story:

Martha was born 10 Aug 1883 and died April 1965. Her mother Etta, married name Allen, was born 3 May 1867, lived her entire life in Oneida County, NY. Etta normally worked as a housekeeper at various homes, the last was the farm of Monroe Bushnell and she may have worked at the Young farm and others. Etta met John when she was living/working at one of these farms. Etta was only 16 years of age when Martha was born. Etta had two other children, George born in 1887 and Grace born in 1891; both now deceased. Etta raised George and Grace by herself . . . . but John and Charlotte Devins took Martha to NYC and raised her as their own. Martha had an excellent upbringing, going to private schools, taking ballet and piano lessons, etc. However, when she got older she rebelled, and I believe she became an alcoholic. She married George Washington Sutter . . . and they had two children, Edna and Alyce . . .

The story began to take on more color. Here was the hint that John Devins was not merely Martha’s adoptive father but perhaps also her natural father. Bob had first heard this suggestion when he was just 12 or 13. He was spending the summer with his Great Uncle George (Martha’s brother) and Aunt Ada Allen, and one evening George handed him the book, John Bancroft Devins, A True Greatheart and told him to read it because it was about his Great Grandfather. Aunt Ada said, “George, stop that!” and the issue was never raised again. But the damage was done. Much later George’s son DeAlton Devins Allen acknowledged that he had heard the story that Martha was the daughter of Grandma Etta and John Devins, but he wasn’t sure if it was true. He could not explain why he carried the Devins name. Bob’s Aunt Alyce left him a written summary of the family history. She told him that John had lived with the same family Etta had been raised in but she emphasized several times that there was “No Relation” repeat “No Relation”. Understandably, young Bob felt she protested too much.

From everything we knew of John Devins, his high moral character and his lifelong commitment to the poor and needy, it seemed to us on the Penfield side of this discussion that it was highly unlikely that he could have been Martha’s biological father. Paul pointed out that John was 26 in the fall of 1882, had just graduated from New York University and was entering Union Seminary. He was preparing to marry Charlotte Penfield the following year. Is it probable that he could have had an illicit relationship with a fifteen year old girl living in Oneida County, New York? And yet, he did know her. Clearly there were some questions to answer.

And so the four of us delved into the mystery of Martha Allen. For the next few weeks, e-mails flew back and forth as we attempted to establish the facts. It was a collaborative effort; each of us brought something to the task. Paul knew the Penfield family history and kept track of the unfolding chronology of events. Holly studied the diaries and letters in her possession and shared important bits of family lore. I went back to the letters and documents from the Silver Bay attic. And Bob told us what he had already learned from his relatives and then searched the internet for census data and other published records when we gave him clues as to what to look for. We relied on E.C. Ray’s biography of John Bancroft Devins for names and dates, though he is not always complete or reliable. For example, he makes no mention of Martha Allen.

We had some difficulty with names. According to Ray, Devins claimed that his father was John Devins and his mother, before marriage, was Ann Mahan, that his father disappeared six months after their marriage, and that his mother offered him for adoption to a French woman, Mrs. Marie, a year after he was born. Two years later his mother and Mrs. Marie surrendered him to the Home for the Friendless. This information came from records of the Home for the Friendless, which presumably Charlotte had helped him find. We were not able at first to locate those records to confirm that account. Family lore, on the other hand, holds that John himself at some point chose the name Devins. He had at first thought to take the name Divine, since he had no parents, was perhaps illegitimate, and knew only that he was a child of his Divine Father, but he was persuaded by a friend to take the name Devins, as being less presumptuous. When he was formally adopted by the family in Oneida County, Ray says, they gave him their last name. “Let us call it Pachman – John Pachman,” Ray writes, perhaps to protect the identity of the family, since he goes on to describe the father in not very complimentary terms. The effect for us, however, was that we could not locate the family, the name Pachman not showing up on the census records, and we wasted time pursuing other families where we knew John had lived, looking for evidence that Etta was there, too.

We were trying to determine where and when John Devins could have known Martha’s mother Etta. We knew her only as Etta Allen, her married name after she married George Allen. Martha also was given the name Allen, though it is not certain that George was her father.

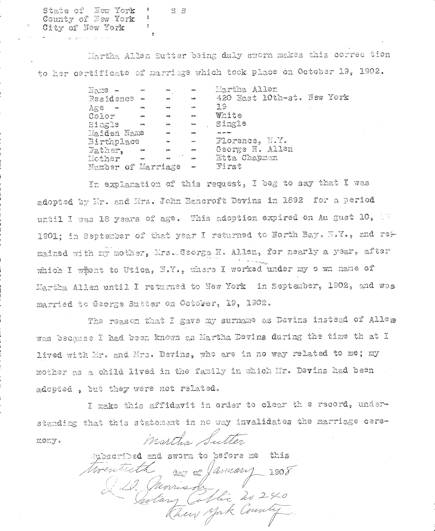

A break came when I discovered another document in the files. This was a legal, sworn affidavit by Martha Allen Sutter, signed on the 20th of January 1908, explaining why she had used the name Martha Devins on her certificate of marriage in 1902.[1] She said that while her name was really Martha Allen, she had been known as Martha Devins for the period of time while she had lived with Mr. and Mrs. John Bancroft Devins as their adopted daughter. She affirmed that Mr. and Mrs. Devins were in no way related to her, that her mother “as a child lived in the family in which Mr. Devins had been adopted, but they were not related.”

In the affidavit, Martha reported that her birthplace was Florence, New York, her father was George H. Allen, and her mother was Etta Chapman. Here was a mine of useful information. Paul immediately recognized that Chapman and Pachman were very similar names and were anagrams. With that clue, Bob was now able to search the census records for the Chapman family of Oneida County, New York. In the census of 1870 he discovered:

Joshua Chapman age 47 farmer

Amelia 36 wife

John 13 son

Ettie 5 daughter

Here at last was the evidence that John had known Etta as his little sister during the period when he had lived with his adoptive parents, Joshua and Amelia Chapman, in Florence, New York. The document also seemed to confirm that Etta, too, was adopted, because Martha says that her mother “lived in the family” in which Mr. Devins had been adopted; she does not say Mr. Devins lived with Etta’s parents. It seems probable that if the Chapmans had reason to adopt John, they had the same reason to adopt Etta. But we had no records to prove that. There was one discrepancy: Bob says that Etta’s tombstone lists her birth date as May 3, 1867. Holly reports that Grandmother Devins’ Red Letter Days book shows her birth date as May 3, 1865. The census report would seem to support the latter.

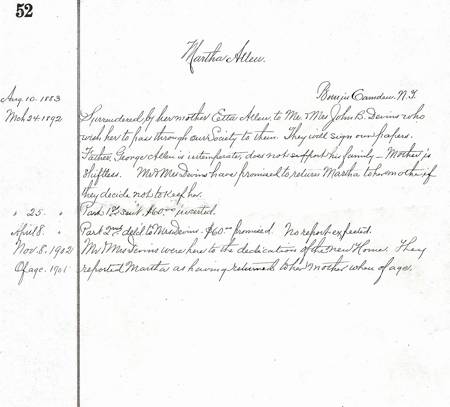

We still hoped to get access to the American Female Guardian Society’s records, to confirm the facts of John’s adoption and get more details of Martha’s adoption. We discovered that the records had been lost for some time but had been acquired recently by the Orphan Train Heritage Society in Concordia, Kansas. In the Fall of 2007, a year after we began our search, they sent us photocopies of John Devins’ and Martha Allen’s records.[2]

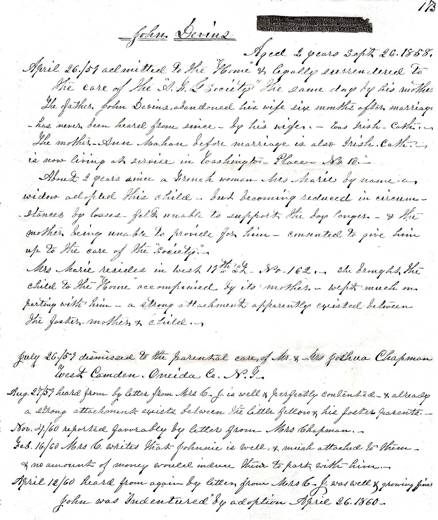

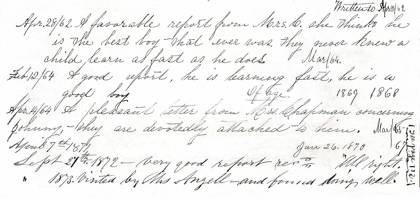

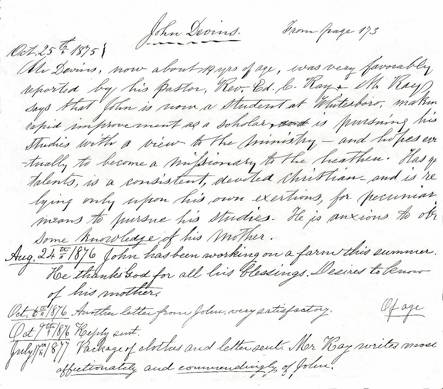

The Devins records[3] seemed to confirm E.C. Ray’s account, which is only to say that he probably consulted the same records that we have now. They are handwritten notes, taken from a ledger, detailing the facts of John’s legal surrender to the Home for the Friendless in April 1859 by Ann Mahan and Mrs. Marie. Both his father John Devins and mother Ann Mahan are described as Irish Catholic. In addition, she is said to be “living in service in Washington Place, No.10.” Paul immediately determined that 10 Washington Place was the home of Cornelius Vanderbilt, confirming another family tradition that John Devins’ mother worked in the Vanderbilt home. As for the tradition concerning John’s name, it would appear that he was John Devins before he was adopted and took back that name sometime after he left the Chapman family. It is a common Irish Catholic name. He may have considered, in jest or seriously, changing his name to Divine, since he did not know his natural father, but in the end he kept his reputed father’s name.

The records also include a short summary of letters received from the Chapman family from time to time over the years between 1859 and 1872. These reports are invariably positive and offer a much different picture of the family from that suggested by E. C. Ray in his biography of John. Even an officer of the Society, who visited the family in 1873, found that all was well. And then there are summaries of letters received from Ray himself in 1875 and also from John in 1876, inquiring about his mother.

The Martha Allen records[4] confirm what we already knew. They establish that it was Martha’s mother, Etta Allen, who surrendered her to the Society in 1892, the father, George Allen, being described as intemperate and unable to support his family. But Etta herself is described as “shiftless”, though we know now that she successfully raised her two other children and kept in close touch with the family, including grandchildren, until her death. It is clear that John and Charlotte Devins arranged for the adoption but wanted Martha “to pass through the Society to them.” Further, the records state that “they promised to return Martha to her mother if they decide not to keep her,” suggesting they had some reservations about the arrangement. There are no other entries in the record until 1902, when it is reported that Martha returned to her mother “when of age”. Evidently the Society had not required John and Charlotte Devins to send the usual periodic reports on their adoptee’s progress.

In May 2008 one more piece of evidence came to light. After months of searching, Bob Busk located Etta Allen’s death certificate. She died in Granby, New York, near the town of Fulton where she had been living with her son George. The certificate indicates that she was born Gertrude Henretta [sic] Cartwright on May 3, 1866 in the town of Florence, New York to [first name unknown] Cartwright and Gertrude Morrison. She died on May 3, 1943 at the age of 77. This would seem to confirm that she was adopted later by Joshua and Amelia Chapman, who changed her name to Etta, but we have no further details. We are left with the mystery that while all three sources agree on her birth day, her birth year is shown as 1867 on her tombstone, as 1866 on the death certificate, and as 1865 in Grandmother Devins’ Red Letter Days book.

Though there remain some important questions to be answered and some facts to be verified, the story of Mattie has taken on shape and can now be told. We can not share the excitement of the chase, but we can relate what we found and ponder what might have been if things had turned out a little differently. The Penfield family tree might have had one more branch.

The Narrative

One of the more serious social concerns of the 19th and early 20th centuries was the problem of orphaned and abandoned children. Poverty, disease, inadequate medical care, and unstable social conditions, especially in cities, left many children with no parents or close relatives to look after them. In almost every community of any size, government and private institutions were established to deal with the problem, and orphanages were almost as common then as nursing homes are today.

The American Female Guardian Society of New York, which has an important part in this story, was among the early private institutions to address this issue. Founded in 1834 as an outgrowth of the Moral Reform Movement[5], its original purpose was to address the needs of poor women in the city, to combat prostitution, and to rehabilitate fallen sisters. One of its efforts was to establish the House of Industry, where women were given work and trained for more respectable employment. In the course of its work however, the leaders of the Society became aware of the large number of neglected, orphaned and abandoned children in the city. Money was raised and The Home for the Friendless was established in 1849, at first to provide a home and education for children at its own facility built on East 30th Street at Madison Avenue[6] and then later, when the number of needy children continued to grow, to arrange placement of the children with families who agreed to raise them, under indenture or adoption, until they reached the age of eighteen. In the last half of the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Society placed thousands of children with families in western New York, Ohio and other states in the Mid-West and West.

It was not chance that brought Charlotte, or Lottie as she was known, to work at the Home for the Friendless. Her parents were early supporters of the American Female Guardian Society.[7] Her mother Mary Irena Treadwell Hubbard was a founding member, and served on the executive committee even before she was married. Her father, Joel Miller Hubbard had helped to purchase the land on which the Home for the Friendless was built. It is interesting to note, however, that her husband Thornton Bigelow Penfield’s first wife, Sarah Ingraham, had also worked at the Home for Friendless in the year between her graduation from Oberlin College and their marriage in 1858.

It was only a year later that John Devins passed through the Home for the Friendless. As noted earlier, his mother, unable to care for him, had given him up for adoption. After three months at the Home for the Friendless, he was placed with Joshua and Amelia Chapman of Florence, New York, near the city of Rome in Oneida County. They were childless and probably glad of the opportunity to adopt a son, though how they made contact with the Home for the Friendless is not clear.[8]

The Chapmans were farming folk. Joshua had inherited his father’s land but they were not very prosperous. Still, they loved John and treated him well. In letters to the Home for the Friendless, Amelia Chapman reported that John was doing well and had formed a close attachment to them. On one occasion she wrote that “no amount of money would induce (us) to part with him.” Hearing only good reports from his foster parents, the Society arranged for his formal indenture to them in April 1860. For the next few years the couple, though poor, looked after him as well as they were able and there is no reason to believe that they abused or misused him. Although uneducated himself, Joshua Chapman insisted that a reluctant John go to school just as he required him to do his regular chores on the farm. Amelia wrote that John “was the best boy that ever was.” She “never knew a child to learn as fast as he does.”[9]

When John was about ten years old, the Chapmans adopted another child, a little girl, Etta, nine years younger than John. Etta’s natural parents also lived in Florence and she was born there. We know their names but nothing more about them or the circumstances of Etta’s adoption. Though John must have had some protective feelings toward his little sister, especially in the difficult years that followed, we have no further information about her and she is not mentioned in Ray’s biography.

At some point the family fell on hard times. They lost the farm and Joshua became a laborer. Either as a result of his misfortune or perhaps as the cause of it, he began to drink, and the family sank even further into poverty. There is a suggestion that Joshua began to treat John, and perhaps Etta, more abusively, but John felt some loyalty toward his adoptive parents. At one point when the family was unable to pay the rent and was about to be evicted from their house, John confronted the sheriff and persuaded him to let the family stay. Thereafter he went to work on other farms, in the local tannery, and in a lumber yard in order to help support the family. Somehow he managed to earn enough money to continue his schooling.

When he was about fifteen, he attended a privately run school taught by a neighbor, Adeline Kelsey, a graduate of Mt. Holyoke, where coincidentally she had been a classmate of Charlotte Hubbard. In later years she remembered him as “an uncouth, unmannerly, and unattractive boy, having been brought up in an unmoral home with no advantages.”[10] Still, she saw some potential in him, and on one occasion when she might have chastised him for some schoolboy mishap, she took him aside and encouraged him to complete his education, go on to college and prepare himself for some useful work, perhaps as a missionary. Thus inspired, John determined that he would go to college.[11]

At sixteen, he told his foster father that he wanted to continue his education. He agreed to stay with them one more year and give them all that he earned, but then he intended to leave. In March of 1873, John left his home and the Chapman family and moved to Vernon Center, a small town near Utica.

It is not clear why John chose Vernon Center, but it turned out to be a happy choice. He found work, with room and board, as a farm hand with Mr. Young, an elder in the Presbyterian Church, and experienced a warm acceptance in the Young family. He also got to know the new minister at the Presbyterian Church, the Rev. E. C. Ray, who became a lifelong friend and mentor and later his biographer. Though he was not able to attend school regularly, he continued his education informally with Ray as his tutor and Ray’s library as his school room. More important perhaps, for his future development, John “got religion”. Through his association with Elder Young and the Rev. E.C. Ray, and his involvement in the church, John found in Vernon Center the Christian faith and commitment that shaped and directed him for the rest of his life.

When Ray was called to a church in Elizabeth, New Jersey, he invited John to come and live with his family there. Before moving to New Jersey, John attended the Whitesboro Seminary near Utica for one year, perhaps his first sustained period of formal education. It was on his way to New Jersey that he stopped in New York, visited the Home for the Friendless,[12] and made the acquaintance of Lottie Penfield. In Elizabeth he continued his active involvement with the Church and his growth in the Christian faith and he managed to complete the equivalent of a high school education. In the fall of 1878, at the age of twenty-two he entered the freshman class of New York University.

A picture of John emerges as an energetic, self confident, ambitious young man, ready to work hard to achieve his goals. We know nothing of his studies at NYU; education seemed always to be a means to an end rather than something he valued for itself. Through dogged perseverance rather than talent, he got himself hired by the New York Tribune, first as a stringer and then, when he learned the craft of writing, as a salaried reporter, and so he was able to support himself through college. He completed his undergraduate studies in 1882 and went on to enroll in Union Theological Seminary.

During these years in New York, John had developed a close friendship with Lottie Penfield and visited her often in New York and at the Hubbard home in Montclair, New Jersey. Lottie had always been very close to her parents and sister Fannie, and they of course had looked after her children while she worked in New York, at least until Thornton went away to school. But Fannie eventually married and left home. Lottie’s father passed away in January 1881 and her mother died in January 1883. John offered her love and security, and would be a father for her children. They were married in October 1883. As a further symbol their union, he took Thornton’s name, Bancroft, as his own middle name.

. . . . . . . .

For all the progress and positive changes that had taken place in John’s life after he left home to make his own way, the condition of the Chapman family in Florence only deteriorated. Joshua fell ill and was unable to support his wife and daughter. Amelia probably found work, but life for them was a struggle. John kept in contact with his foster parents, and when he was able, he sent them money. When his father died, perhaps while he was in college, John returned home to be with his mother. He paid off the medical expenses and covered the cost of the funeral, and he continued to support Amelia, and his sister Etta, until his mother remarried some time later.[13]

We know nothing about Etta during this time. She was probably aware of her big brother’s help and looked forward to his occasional visits. She may have attended the local school for a few years but very likely had to go to work when she was still very young to help support the family. Her father’s death and mother’s remarriage must have left her feeling abandoned – or perhaps liberated. By then she, too, had learned to make her own way. From the census of 1880, we learn that Etta, aged 15, was living as a “houseworker” in the home of Patrick and Margaret Maloney in Florence. They had four sons, aged 20, 18, 16, and 14. They must have been recent immigrants because all had been born in Ireland. We know nothing more of the family or the circumstances of Etta’s employment.

Life changed for Etta with the birth of her first child, Martha, on August 10, 1883. Since questions have been raised with regard to Martha’s paternity, we need to address the issue. Unfortunately, we have not been able to find a formal record of her birth, a certificate which would show her father’s name. Knowing what we do of John Devins’ character, of his work in New York and attendance at Union Seminary in the fall of 1882, of his relationship with Lottie, his “sibling” relationship with Etta, and simply distance and opportunity, it seems highly unlikely that he would be the father. There would have been other candidates closer by. As far as we know, Etta never left Florence and Martha was born there. If Etta was unmarried, someone must have given her shelter and support, but it would have been difficult for her in that small community.

Except for the rumors and suggestion of illegitimacy, it is easier to accept the simpler, more direct explanation. The American Female Guardian Society records of 1892 report that Martha’s father was George Allen,[14] and in a sworn statement issued years later, Martha confirmed that her father was George H. Allen. Her daughter Alyce, who later lived with her grandmother Etta, reported that as well. Although we have found no formal record of their marriage, George and Etta had two more children, George Jr. born in 1887 and Grace in 1891, before they separated in about 1892.[15] By that time, Martha had already been adopted and was living in New York. Etta did raise George and Grace. The census of 1900 shows Etta living as a housekeeper in the home of Monroe Bushnell in North Bay, ten miles south of Florence, with her children George, 12, and Grace 9.

But there is the troubling fact that Etta gave Martha up for adoption. We do not know why. In recalling the family history, Alyce wrote, “Martha was 4 or 5 years of age when she moved to NYC to be raised by Dr. John Devins.” Alyce is probably mistaken in respect to the timing, because we know that John and Charlotte Devins did not take her until 1891 when she was eight, but her memory that they came and took Martha with them to NYC suggests that Etta, for whatever reason, had appealed directly to them, and John, compassionate as always, and especially sympathetic to his sister, agreed to look after her daughter. To formalize the relationship they asked the Home for the Friendless to arrange for the legal surrender and adoption.

. . . . . . . .

After their marriage in October 1883, John and Lottie made their home in New York. Thornton and Irene already knew John well. Thornton later recalled that the marriage “brought great relief to (mother) in the guidance of my sister and myself as well as in financial matters.”[16] They had called him “Uncle John”. Now they learned to call him “Father”. Irene was 13 and lived with her parents. Thornton was 16 and continued his studies at the St. Johnsbury Academy in Vermont. Lottie may have resumed her work at the Home for the Friendless, perhaps on a volunteer basis, but more likely stayed home and gave her full attention to Irene. John jumped right back into work.

It is amazing that he found time for the wedding. He was enrolled in Union Seminary and working full time for the New York Tribune. He was not a brilliant student, had little interest in abstract theology, and was almost felled by Hebrew. But he persevered. On the Tribune staff he was given more and more responsibility until he was appointed night editor. Ray gives a description of his days. He returned home from the office at two or three in the morning, slept until ten when Lottie woke him and gave him breakfast, rushed up to Union where he attended classes and studied until six. Lottie might meet him somewhere for dinner at a restaurant and then accompany him to the Tribune office. She returned home alone and he took up his night work. There was not much family time, but they seemed to be happy.

It would have been a terrible shock to Lottie, as well as Thornton and John, when Irene contracted measles and died suddenly in 1885. She had already lost her first husband and a baby daughter. Irene, almost fifteen, must have been a close companion and friend. Thornton returned home the following year and lived with his parents while attending college at Columbia and seminary at Union.

John graduated from Union Seminary in 1887 and accepted the position of minister at Hope Chapel, a mission outreach of the 4th Avenue Presbyterian Church, on the Lower East Side of New York. If anything, his work load increased. He continued working on special assignments for the Tribune and he had full responsibility for all that happened at Hope Chapel. The family lived in a simple apartment above the mission. While he was spared the commute to Union, he had to deal with a constant stream of visitors, parishioners and petitioners, on business or pleasure. He was involved not only in the expected Sunday services, week day prayer meetings, youth work, pastoral calls, and other needs of his members but also with a myriad of social outreach activities to the working class and immigrant population on the East Side.

His work as a reporter with the Tribune brought him into contact with the political, business, and religious leaders of the city. His work at the Chapel put him in close touch with the laboring classes, the needy and the homeless. He seems to have been at ease in both groups and with those in between. He made no distinctions among Protestants, Catholics or Jews and addressed the concerns of all. The Mayor appointed him to various commissions, Jacob Riis visited him and wrote about his work, Theodore Roosevelt knew him when he was N.Y. Commissioner of Police, and Howard Taft wrote the Foreword to his book on the Philippines. None of this attention distracted him from his true mission to the poor who needed his help.

Lottie had suffered serious illness and was never very strong, but she was involved in the activities of the Chapel and supported John in his work. She certainly shared his concerns and commitment. According to family lore, John never forgot his own uncertain origins and therefore treated everyone he met as quite possibly his brother or sister.

It is into this family, and this environment, according to Lottie’s Red Letter Days book for March 10, that “Mattie Allen came in 1891.” She was eight years old.

. . . . . . . .

It must have been difficult, if not traumatic, for Mattie to be separated from her mother, taken by two strangers to the big city, and to have to adjust to a life so entirely different from anything she had known in Florence. No matter how much love and attention her new parents showered on her, she must have felt her loss, and it may have taken her a long time to appreciate what she had gained. John and Charlotte certainly looked after her well. We are told she attended private schools and took piano and ballet lessons. She must have participated in the life of the Chapel, attended meetings and socials, and was pampered by the ladies of the church. We can imagine that she enjoyed the attention of her big brother Thornton. There may have been problems, as well. But, in fact, we know very little of Mattie’s life over the next ten years.

Had Lottie continued to keep a journal, as she did in India, we might have a better picture of Mattie and of Lottie’s own feelings about her, but even in India her writing was sporadic, and for this period she wrote not at all. We do have letters, but letters are only written when one of the parties to the correspondence is away and do not give an idea of what was happening in the everyday, routine times at home. Lottie seems not to have kept her letters from John, though we have a number of the letters she wrote to him. From them we know that he wrote her faithfully when he was away, but we do not have his letters. Thornton’s wife Martha Mee kept almost every letter ever written to her, including those from Lottie, John, and her husband, and even some of her own. These letters give us some insight into Mattie’s life in the Devins household.

While he was attending Union Seminary, Thornton spent two summers in Minnesota, on behalf of the Presbyterian Board of Home Missions, organizing Sunday Schools. In the summer of 1891, only a few months after Mattie arrived, Lottie accompanied him and stayed for over a month. They lived in Northfield and visited churches and communities in the nearby counties. We have five letters which Lottie wrote to John in June and July. They are tender and loving in tone. She addresses him “Precious husband” or “My dearest John” and closes with “This happy wife” or “Your Lottie”. She describes what they are doing and the progress they are making, writes with pride of her son, inquires about John’s work, is concerned about his health. She remembers when he is taking the older ladies of the church to Coney Island and wishes him well when he is to give a special lecture somewhere. She ends her first letter, “Love to our little girl.” In the five letters there is only one other mention of their little girl, a cryptic question after she has commented on some other developments in the church, “And how about Mattie?”

From 1889 until their marriage in 1894, Thornton and Martha Mee Martin carried on a regular correspondence. Thornton’s earliest letters are addressed, “My dear Miss Martin”. The last, “My own, my precious Martha”. We understand they were more interested in each other than the rest of the world, but they write about other things and Mattie makes a few appearances.

On October 24, 1892, Martha writes from her parents’ home in Brooksvale, Connecticut in response to a letter from Thornton that is missing, “I am glad you have so promising a little sister and hope the adoption will prove of mutual benefit.”

On June 24, 1893, Thornton writes from Ocean Grove, New Jersey, “The water is just right and the great waves fine. I’ve just come up from the ocean where Will Harmon (and other friends) and my little sister Mattie, together with yours truly, have been bathing for the last half hour and catching sand crabs in between dips.”

On September 12, 1893 he writes from New York, “The evening is before me, and I am going to begin it by writing to you. Little Martha is at my side, and as time hangs heavy on her hands with Father and Mother gone, I have suggested she write to you. I will enclose her note with mine. Don’t feel you must answer it, although a little note to her, tucked in some future letter to me, would be gratefully appreciated.”

On November 30, he writes from the Devins apartment on East 4th Street, “This has been a happy Thanksgiving day in our little home. We were all here for a quiet day, in good health, with no worry, and bright prospects for the future. . . . After breakfast Mattie and I went out to take a turkey to a poor family and then we went to church and heard a good address. Uncle DeWitt Van Winkle and my Aunt Fannie came to take dinner with us as usual.”

On December 23 he writes to wish Martha the joys of the season, “A merry Christmas to you! May all the sweetest joys of the Christmas tide be yours – and I believe they are. God has indeed been very good to us both, and we thank Him – do we not, my love? . . . It is Saturday evening, and the preliminaries for the celebration in the Chapel are settled, so I have the liberty to write. I bought a pretty sterling silver button hook and a nail file for Georgia[17] today. I have an after dinner coffee pot & alcohol lamp for Mother, a toilet set for father, a pair of hassocks, one for each, a xylophone for ‘Martha’ and a box of stationery for Hannah.”

Another paragraph illustrates the pace of life in the Devins home: “Tomorrow I go to West Hoboken to speak in the afternoon. In the evening I expect to preach the Christmas sermon for Father. Poor man, he is about used up. The condition of the unemployed in our city is growing steadily worse and Father is head over heels into all the efforts to help the poor. It is beautiful to be able to do this, but with him it is a perfect passion. It is his hobby and he is riding it for all it is worth. Well, the Lord is using him in this work, and I know no one better qualified to undertake it than Mr. Devins.”

Thornton Penfield and Martha Mee Martin were married on September 12, 1894, and the surviving letters from 1894 reflect that preoccupation. After the wedding they moved to a house in Brooklyn. Thornton had graduated from seminary and was now working with the Young People’s Department of the Presbyterian Board of Home Missions. He was constantly on the road, traveling all over the country, returning home to speak at churches and Sunday schools in the New York area. He wrote to Martha Mee regularly but there are no more references to Mattie. Of course he was no longer living on East 4th Street and had little direct contact with her. Occasionally when Martha Mee is visiting her parents in Connecticut, he writes of having dinner with Father and Mother, but still there is no mention of Mattie.

Lottie immediately accepted Martha Mee as her daughter. She wrote often and lovingly, especially when Thornton was away, and visited as frequently as she could. She was no less excited than the parents when Charlotte Martin Penfield was born in July 1895, was as happy to welcome Thornton Jr. in May 1899 and Paul in August 1901. Her letters are full of questions about the children, grandmotherly advice when they are sick. In August of 1901, before Paul was born, Lottie took six year old Charlotte with her to the conference center in Northfield, Massachusetts. In her letters to Martha Mee, she delights in Charlotte’s poise, her intelligence, her politeness. She loved showing off her granddaughter to friends. Later she loved to describe the boy’ antics. We hear almost nothing of her own daughter Mattie.

Once, on January 28, 1900, when they are getting ready to go to a conference at Northfield and regretting that they can not make one last visit to Brooklyn, Lottie writes, “We have asked Mrs. Davis of Bayonne to take Martha while we are gone. She is to go back and forth to school. You know old Mr. Davis’ family that used to live in Bloomfield, the school inspector. We shall feel safe to have her there and they will look after her lessons, etc.”

It is worth quoting more of that letter: “Father is sleeping away, poor man. He has been working very hard and is tired – he tries to catch up on his short hours of rest at nights, on Sunday.”

With all their comings and goings, extended visits out of town, even a trip to Europe in 1895, they had probably left Mattie in the care of their housekeeper many times. Why did their 16 year old daughter need special care this time?

In fact we can discern that all was not well. Perhaps the adoption was in trouble from the start. We know nothing about the first eight years of Mattie’s life and very little more before she reached the age of eighteen. With Lottie we want to ask, “What about Mattie?” Perhaps she was just a difficult child. Maybe that was part of the reason Etta asked John to take her. But that is not the impression we have from Thornton’s references to her in his letters. There she seems to be a typical, sweet little girl, “promising” in Martha Mee’s words, happy to be doing things with her big brother.

But Lottie seems never to have taken to Mattie. We see none of the love and joy that she expressed when Martha Mee joined the family or when the grandchildren arrived. Her silence speaks for her feelings. On her trips out of town, she leaves Mattie in the care of John and the housekeeper and never asks about her. As far as we know, she never took Mattie to Northfield, even on that occasion in August of 1901 when Mattie would have been out of school and could have helped look after little Charlotte. Thornton arranged trips for his “Sunday School girls” and asked his mother to chaperone. Was Mattie invited to go? She is not mentioned.

It was probably John’s decision to adopt Mattie in the first place, but Lottie had worked at the Home for the Friendless and should have been sympathetic. Perhaps Mattie only reminded her of the daughters she had lost. Irene’s death was too recent, and she did not have the emotional capital to invest in another child, particularly one with emotional problems of her own.

And John, who had time for every other needy soul, had little to share with Mattie. He worked 16-18 hours a day and spent Sundays, after services, catching up on his sleep. In one of the rare letters we have in his hand, he wrote to Martha Mee a month after Charlotte’s birth, apologizing for not writing sooner: “Strange as it may sound, Adam-like though it may appear, the good wife, the other good one, is responsible for the delay. She insists – I will use no stronger word, certainly not one that begins with n – she insists that her husband must spend part of every twenty-four hours in sleep, no matter how large may grow the pile of unanswered correspondence or the piles of unread newspapers.”

For all the advantages her parents provided her, Mattie was still missing the most important thing. She may have become a rebellious teenager, not the first or the last, but she had some reasons for discontent. How her rebellion played out is not entirely clear – again there is nothing in the letters to suggest there was a problem, except for the time when she was sent to stay in Bayonne when they were out of town. But the issue was coming to a head.

On September 29, 1901, writing to Martha Mee, who was away with the children in Connecticut, Thornton wrote, “Now for some news. Martha Devins has actually gone, bag and baggage. She went this morning. Last night Father found out that Martha was again deceiving him and following that up unearthed a series of deceptions and falsehoods carried on right up to last night. That brought about the conclusion of the matter and even Father feels that it is a hopeless case. So this morning he again sent Martha’s trunk off. It had only been back a few hours – and he took Martha himself on the morning train for Camden, N.Y. [18] The end came quickly and it took Martha so completely by surprise that she had no time to shape any defense and she had to give up, baffled for once. In some ways I am glad that he did not send Martha off on Wednesday, for if she had gone then he would always have thought that he ought to have given her another chance. Now he gave her that chance and she has thrown it away and he feels that he has done all that he can and is more easy in consequence.”

Two days later he wrote again, “Father returned yesterday from taking Martha up. He seems quite reconciled to the step, and I guess this time it means business. Martha persisted in lying even when Father left her in Camden, admitting her guilt in part and denying other things that were doubly proved beyond a doubt, but in ways so that Martha did not know that Mr. Devins had the proof.”

We do not know what she was admitting or denying but her behavior was serious enough that John Devins knew she could not remain in New York and should go back to her mother. She still thought she could stay. Perhaps no one at that point, not even Mattie, knew that she was pregnant.

That was not quite the end of her contact with John and Lottie. Two months later, on November 4, 1901, Lottie wrote Martha Mee to wish her a happy birthday: “I am sorry that we cannot get over to see you this week, but we start for Dr. Devins’ old home in Camden, New York on Tuesday and will not be home until Thursday, skipping your important day.” She can not bring herself to use the names Etta and Mattie or explain the purpose of their visit.

. . . . . . . .

In the sworn statement she made in 1908, about which more will be said later, Martha said: “I was adopted by Mr. and Mrs. John Bancroft Devins in 1892 for a period until I was 18 years of age. This adoption expired on August 10, 1901; in September of that year I returned to North Bay, N.Y. and remained with my mother, Mrs. George H. Allen, for nearly a year, after which I went to Utica, N.Y., where I worked under my own name of Martha Allen until I returned to New York in September 1902, and was married to George Sutter on October 19, 1902.”

That is not the whole story. Bob Busk remembers the occasion in about 1935 when his mother Edna, Martha’s oldest daughter, heard that her brother had died. She had first met him only three days earlier. Her sister Alyce, in Utica, had discovered their long lost brother, William Heib, living somewhere in upstate New York and had brought him to visit Edna in Brooklyn. Bob’s sister Dorothy remembered the visit and her negative feelings. “He had a sinister type way about him and his girlfriend was like a brassy type showgirl.” She felt he was not part of HER family. He was involved in a robbery a few days later and was shot dead by a policeman as he tried to run away. Dorothy never spoke of this and tried to put it out of mind, but Bob persuaded her to tell the story some years ago, and then both put the skeleton back in the closet. Bob remembered it again when he learned of Martha’s unexpected trip back to North Bay and return to New York a year later.

So it would seem that Mattie was pregnant when she arrived in North Bay. When Etta found out, she must have contacted John immediately, and in spite of all that had happened, true to character, he and Lottie must have traveled to Camden and North Bay that November to offer Mattie counseling and advice. Through his contacts with the Home for the Friendless he may have found a family willing to adopt her child. He would have advised Mattie to stay away from New York, to avoid the temptations of the city, and to try to start a new life in Oneida County.[19] When she had had the baby and made arrangements for his adoption by the Heib family, Mattie worked for a very short time in Utica. But love trumped fatherly advice and very quickly she raced back to New York to marry George Sutter, presumably her child’s father. For John and Lottie that would have been the last straw.

George Washington Sutter lived at 420 East 10th Street in New York in a family owned building, not far from Hope Chapel and the Devins home at 339 East 4th Street. As a young man he had lost a leg when he was run over by a horse drawn milk wagon. In spite of that, he became a life guard at Coney Island. We do not know how he and Martha met, perhaps at Coney Island, but once they knew each other, it would not have been hard for Martha to slip out and see him, especially if her parents were not at home. When John and Lottie became aware of this friendship and of Martha’s secret trysts, they would have been very worried about her, not least because they might have suspected that George had introduced Mattie to alcohol. But clearly, Mattie found ways to continue the relationship, with the consequences we have seen.

When Mattie returned to New York in 1902, she and George were married and moved into an apartment at 420 East 10th Street. The Sutter family owned the building. George’s mother had nine children and most rented an apartment from their parents after they got married. George and Martha had two children, Edna born in 1905 and Alyce in 1908. Even though George and Mattie were surrounded by his family, money was a problem. Mattie had probably started drinking. She approached John Devins for help, perhaps persuaded that he still owed her something. It appears that John rebuffed her. Prior to their setting off on a nine month world tour in 1903, John set his house to order, arranged insurance, rented a safety deposit box, and registered a cable address. In a note to Thornton he wrote, “Martha Allen has received all the money she is intended to have or to which she may think she has the slightest claim. There is nothing due her of any sort or kind, either in money or in goods.”

But there was one last encounter between Mattie and John Devins. In 1908, Mattie executed the sworn affidavit, referred to before, most probably at John’s behest, because he received and preserved the original document. In it she explained why she had given her name as Martha Devins on her marriage certificate: “The reason that I gave my surname as Devins instead of Allen was because I had been known as Martha Devins during the time that I lived with Mr. and Mrs. Devins, who are in no way related to me; my mother as a child lived in the family in which Mr. Devins had been adopted, but they were not related.”

Why did John feel it was necessary at this time for Mattie to make such a statement? Perhaps he needed it to set the record clear. It may be that Mattie had floated the rumor that John Devins was indeed her natural father, that he had abandoned her mother 25 years ago and was now abandoning her. This would have been an attack on his good name and reputation that he could not afford and would not tolerate. He was a minister, active on the Lower East Side, and very well known in the city. The affidavit served as a caution to Mattie. He had already shown that he could use the law and the courts when he defended a Hungarian woman he had befriended against an unjust attack. Now he could warn Mattie that he would take her to court if she continued to spread that rumor.

The break was now complete. Though E.C. Ray never mentions Mattie in his biography, the account he gives of John Devins’ life and the eulogies and memorials he appends to his book would suggest that Mattie’s adoption was one of the few failures John ever experienced that he could not set right by hard work, good will, and perseverance. It is a shame that the relationship had to end in bitterness. It had been a painful experience. Those who knew the story never spoke of it, and later generations of the Penfield family never learned of their cousin Mattie.

. . . . . . . .

For Mattie the situation was even more tragic. According to Sutter and Allen family lore, Martha was now a confirmed alcoholic. She had no support. There was no counseling or twelve step program to help her. Addiction was not well understood. For good Christians at that time, like John and Lottie, drinking was a matter of personal choice, a moral failing, and their advice to her would have been to repent, give up her sinful ways, and return to the Lord. For Mattie that was not enough.

The consequence for her was that she lost her husband and her children. Martha’s name does not show up in the census of 1910. We do not know where she was, but her husband George was still living, without his wife, in the family owned building on East 10th Street with one of his brothers. Edna was living with her Sutter grandparents in the same building. And Alyce, just two years old, is listed as the adopted child of a traveling salesman William Marvin and his wife Margaret at their home on West 15th Street.

Mattie was not entirely out of the picture. The 1920 census finds her living alone in a rooming house on 7th Avenue. She is listed as a waitress in a restaurant. She may not have been able to take care of her family, but she must have loved her girls and kept in contact with them. And she made sure that they knew about their Allen relatives. When Alyce’s adoption failed for some reason, Mattie took her to live with her grandmother Etta on Monroe Bushnell’s farm in North Bay, and that is where she grew up. After high school Alyce attended a business school and then went to work with a company in Utica. She never switched jobs, she never married, and she remained in Utica for the rest of her life. She was in close touch with her grandmother Etta and with her Uncle George and Aunt Ada, and her Aunt Grace lived with her in Utica from 1967 until her death in 1975. Alyce died in 1992.

Edna was raised with her cousins in her Sutter grandparents’ home in New York. After her marriage she had three children, Bob Busk, whom we know, and sister Dorothy and brother Al. She, too, kept in touch with the Allen family and sent Bob, when he was 12 or 13, to live with his Great Uncle George and Aunt Ada in Fulton, New York one summer. He remembers meeting his grandmother Martha once and his great grandmother Etta once, but when he was very young.

Etta lived as a housekeeper at Monroe Bushnell’s farm in North Bay for many years. When Bushnell died in 1936, she seems to have inherited the farm or at least had the right to live there. Contrary to the Home for the Friendless description of her as “shiftless” she seems to have been a remarkable woman. She worked all her life, eventually serving as a housekeeper for a family of six while raising her own two children and then her granddaughter. She became a beekeeper and self taught landscape painter. She was an active participant in her community, a member of the Ladies of the Grand Army of the Republic and a member of the North Bay Rebecca Lodge. She lived in North Bay until about 1942 when she went to live with her son George and his wife Ada in Fulton. She died in 1943 and is buried in North Bay.

Mattie continued to live in New York City and was employed, according to family lore, as a cook in various hotels and restaurants. In spite of personal difficulties, she seems to have worked to hold her family together. In 1956 she moved to Utica to live with her daughter Alyce. She died in 1965 when she was 82 years old.

Mattie’s grandson is Bob Busk. His wife’s name is Charlotte. He must be a Penfield! Let’s invite him to the next family reunion.

Appendix

1. The American Female Guardian Society and Home for the Friendless.

2. The Records of John Devins from the American Female Guardian

Society files, 1859-1877.

3. The Records of Martha Allen from the American Female Guardian

Society files, 1883-1902.

4. Sworn affidavit of Martha Allen Sutter, January 20, 1908.

1. The American Female Guardian Society and Home for the Friendless

Engraved certificate from the American Female Guardian Society & Home For The Friendless issued in 1857, showing the Home for the Friendless on East 30th Street, New York City, on the left, which backs up to the Chapel and offices of the American Female Guardian Society on 29th Street, on the right. This document was printed by J. Bien, New York.

The American Female Guardian Society was founded in 1834 in New York to address the needs of poor, usually single, working women in the city. In 1849, as its program and services grew, it was able to purchase land on 30th Street, between Fourth and Madison Avenues, for the construction of its offices, a chapel, and the Home for the Friendless, a shelter for destitute women and homeless children, pictured above. It remained in those premises for 52 years.

Increasing congestion and rising land values in Manhattan led the Society to move to the Bronx 1902, where it had erected a large Beaux-Arts building to accommodate 200 children. Dr. and Mrs. John Devins contributed the furnishings for the secretary’s office. The building was located on Woody Crest Avenue, near what was to be Yankee stadium, and while the American Female Guardian Society and Home for the Friendless was its official name, it became known simply as Woodycrest. Over the years its mission changed, though it continued to work with orphaned or handicapped children. Financial difficulties led it to merge with the Happy Valley School in Pomona, Rockland County, New York, in 1974, which had a similar history and mission. Woodycrest Five Points Child Care, later renamed Greer-Woodycrest Children’s Services, continued to operate until the 1990s when bankruptcy forced it to close. The site is now occupied by a golf course.

2. The Records of John Devins from the American Female Guardian Society files, 1859-1877

American Female Guardian Society files held by the Orphan Train Heritage Society of America, P. O. Box 322, Concordia, Kansas 66901

3. The Records of Martha Allen from the American Female Guardians

Society files, 1883-1902

American Female Guardian Society files held by the Orphan Train Heritage Society of America, P. O. Box 322, Concordia, Kansas 66901

4. Sworn affidavit of Martha Allen Sutter, January 20, 1908

References

Devins, John Bancroft, The Classic Mediterranean. New York: American Tract Society, 1910.

Devins, John Bancroft, An Observer in the Philippines. Boston: American Tract Society, 1905.

Fletcher, Robert Samuel, A History of Oberlin College. Oberlin, Ohio: Oberlin College, 1943.

Our Golden Jubilee, A Retrospect of the American Female Guardian Society and Home for the Friendless from 1834 to 1884. New York: American Female Guardian Society, 1884.

Penfield, Florence Bentz, The Genealogy of the Descendants of Samuel Penfield. Reading, Pennsylvania: Harris Press, 1964.

Penfield, Thornton B., Memoirs. edited by Ruth Penfield, 1958.

Ray, E. C, John Bancroft Devins, A True Greatheart. New York: Association Press, 1912.